Author: Doghouse

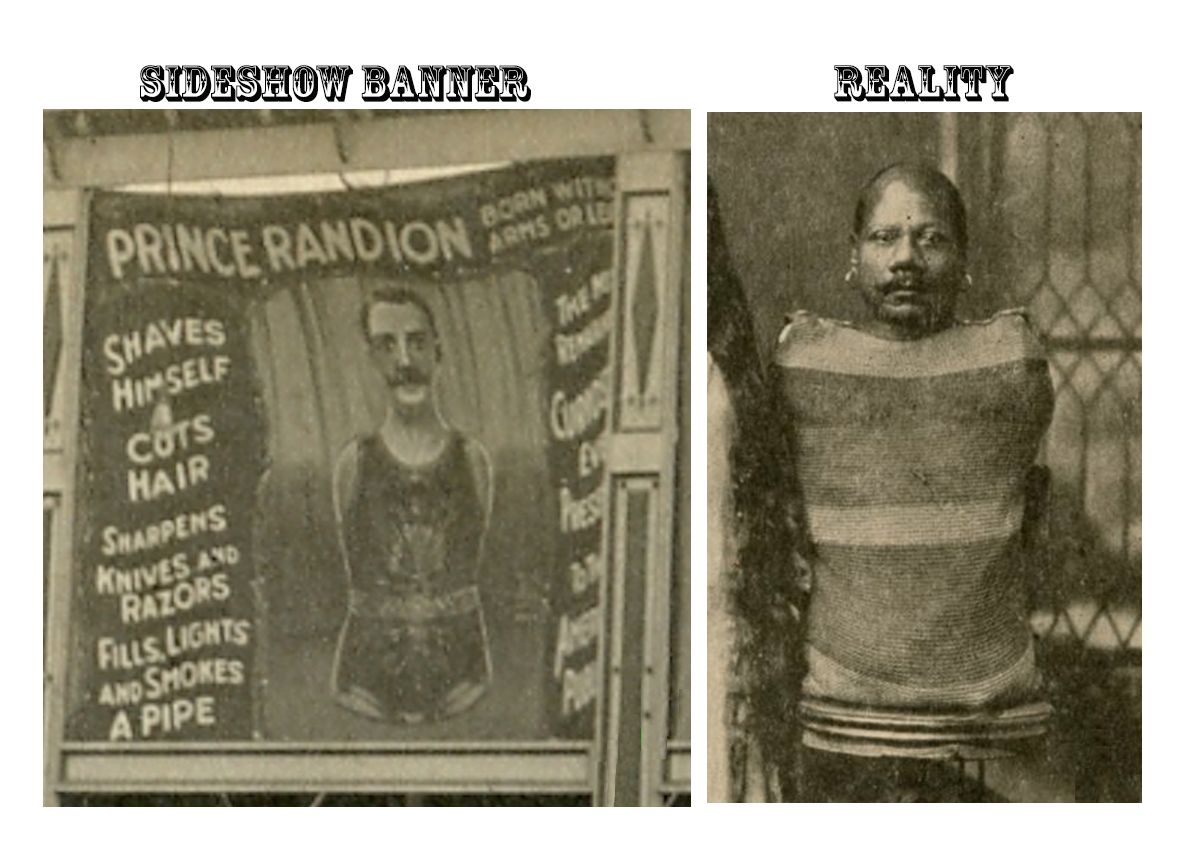

Savage Sideshow: Exhibiting Africans As Freaks, by John Strausbaugh

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on Savage Sideshow: Exhibiting Africans As Freaks, by John Strausbaugh

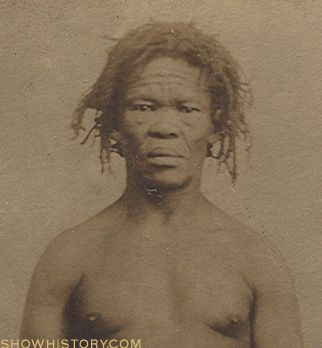

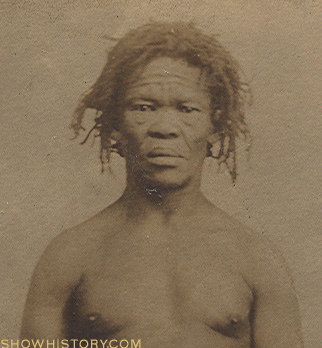

ABOVE: Clico, Authentic African Bushman. Detail from 1920’s real photo postcard.

by John Strausbaugh

From the 15th through the 19th centuries, Europeans were engaged in a prolonged epoch of exploration and expansion, during which they would exploit their technological advantages to extend their power and influence around the globe. But only a minority of Europeans actually ever saw the lands and peoples they were conquering; the vast majority of Europeans, excepting sailors and those who shipped out or were packed off to the colonies, lived and died very close to the place where they were born.

So the explorers, sailors and adventurers brought the world to them. Along with their stories, they hauled back specimens of exotic plants, animals and cultures by the trunk-, boat- and caravan-load. Much of this nimble-fingered acquisitiveness was in the service of genuine scientific discovery; but much was purely in aid of show biz. Humans have an insatiable curiosity for the rare, the exotic, the freak and the new. The reality tv and Jerry Springers of the early 21st century can trace a direct lineage back through the freak shows and circuses of the early 20th, to Barnum’s American Museum in the 19th, to the 17th-century cabinet of curiosities–right back to the first West Africans kidnapped to Portugal to amuse and edify the court of Prince Henry the Navigator in 1441. In the era of global European expansionism, it mattered little to the audience if the rarity on display was a Saharan camel, a two-headed goat, a Hottentot or a Navajo. It was all curious and fascinating, sometimes frightening, sometimes sexy. Most importantly, it was out of the ordinary, appearing in places and at a time when the ordinary could be very ordinary indeed.

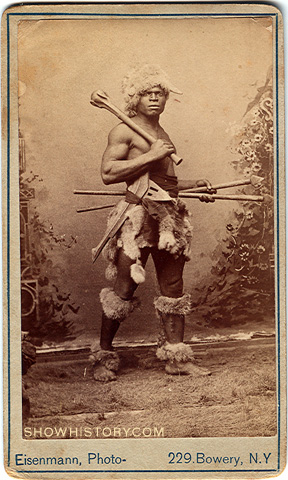

ABOVE: Zulu Warrior, photo by Charles Eisenman (ca. 1875)

“One reads of live Eskimos being exhibited in Bristol as early as 1501,” Africanologist Bernth Lindfors writes, “of Brazilian Indians building their own village in Rouen in the 1550s, of ‘Virginians’ canoeing on the Thames in 1603, and of numerous other native specimens from the New World, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands being conveyed to European cities and towns as biological curiosities…” In the 1850s, a pair of diminutive Bushmen entertained the patrons of an inn outside London, singing English songs and playing the piano. In the same decade, a troupe of Zulus performed in front of a painted “African” backdrop; they pretended to be completely unaware of the audience as they went about what was supposedly their daily routine. This conceit that audience members were inobtrusive observers, like anthropologists in the field, would be continued in the “native village” displays that were de rigeuer for every Victorian and Edwardian World’s Fair. Exotic performers regularly appeared on the bill at lecture halls and music halls, county fairs and amusement parks. They worked the vaudeville circuit throughout its span. Barnum’s circuses and his American Museum were never without rare and strange human displays, from Eng and Cheng to Madagascar albinos to Zip the pinhead.

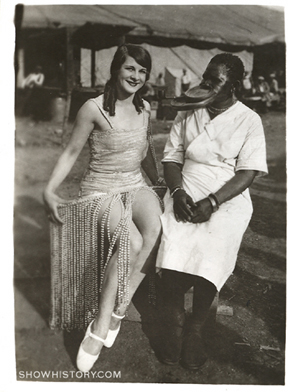

ABOVE: Ubangi woman with show girl on Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus 1931.

Of all the “primitive” and “savage” humans who appeared in these settings, none provided such consistent fascination as Africans. They were Black, therefore the least White of all peoples on the earth. In the Great Chain of Being, with European Man at the apex, they occupied the lowest rung of humanity, closest to the beasts. When Darwin’s theories of evolution were being debated from 1859 on, Africans–especially Pygmies, who had been captivating the imaginations of Europeans since the time of Homer and Herodotus–were widely seen as representing an early stage of evolutionary development, far from Civilized Man, much nearer to the primates they supposedly resembled. Thus Bronx Zoo director William Temple Hornaday had no misgivings about exhibiting the Pygmy Ota Benga in a cage next to that of an orangutan in 1906. Forty thousand people a day flocked to see the “wild man.”

As the enduring interest in Pygmies indicates, most fascinating of all were Africans who combined their inherent exoticism with some aspect of freakishness. Ubangi women wearing their lip-stretching disks were never-fail attractions at world’s fairs and expositions well into the 20th Century (and were caricatured in innumerable comics and animated cartoons).

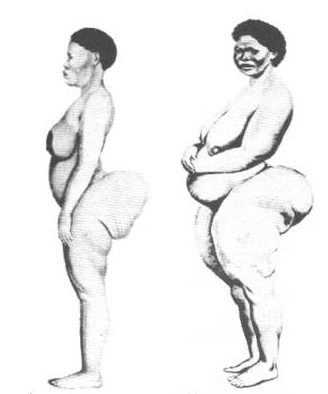

ABOVE: Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus.”

The most famous example of this eroticized freakishness is Sarah Baartman, who first appeared in London in 1810 billed as the “Hottentot Venus.” Hottentot is an invented European name for a South African nomadic people who call themselves the Khoikhoi. They probably got the Hottentot nickname, derived from the Dutch for “stutterer,” because of their clicking language. The Khoikhoi had repeated and usually violent encounters with Europeans from as early as the 1480s on, as the Cape of Good Hope became a busy midway stop for trade voyages to and from Portugal, Holland, England and the Orient. No less an adventurer than Vasco de Gama battled with the herdsmen, and was wounded by them. As the Dutch settled the Cape and spread outward, the Khoikhoi were pushed off their ancestral lands, with many murdered, and others taken as laborers or, like Baartman, as domestic servants.

Baartman caught the Europeans’ attention because of her striking symptoms of steatopygia, an extreme enlargement of the buttocks. In European eyes this made her an anatomical oddity and yet “a most correct and perfect Specimen of [her] race,” as she would be advertised. In other words, she wasn’t a freak within her own people–they were all freaks. Baartman went to London voluntarily as a paid performer, but it’s clear that she was never happy or comfortable being gawked at. Like Jayne Mansfield’s huge hooters, her giant booty became the talismanic focus of much sleazy eroticism–early London audiences, who were mostly male, were even allowed to touch it. This ended after a legal challenge from an Abolitionist group. Baartman moved to Paris in 1814, where her display was less sideshow, more serious ethnology, but it doesn’t seem to have been much less degrading. By the time of her death in 1816 she had sunk into drug addiction and part-time prostitution.

As the final indignity, her body was carved up in autopsy, and her skeleton, brain and genitals were put on display at the Paris Musee de l’Homme–where they remained until 2002, when Thabo Mbeki’s South African government finally convinced the French to send her home. Speaking at her gravesite, the characteristically outspoken President Mbeki said, “It was not the lonely African woman in Europe, alienated from her identity and her motherland, who was the barbarian, but those who treated her with barbaric brutality.”

“Authentic” Pygmy villages and actual troupes of Zulu warriors remained in such high demand into the first few decades of the 20th Century that showmen sometimes ran out of real Africans to exhibit. They turned to African American ringers, some of whom made excellent livings impersonating their wild and savage cousins. One of the most successful impostors was Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola, celebrated vaudeville performer, university lecturer, soldier of fortune, friend to the crowned heads of Europe, and author of the memoir ‘An African Savage’s Own Story,’ published by Knopf in 1929. LoBagola claimed to be a Black Jew from the “African Bush,” but he was really from Baltimore, where he was born Joseph Howard Lee. Despite his impoverished start and lack of education, despite skeptics continually questioning his authenticity, despite a series of scandalous arrests and prison time related to homosexual activities, Lee/LoBagola maintained a long and colorful career as a faux African. His homosexuality, rather than his false identity, was his undoing; he spent his last thirteen years in Attica, convicted of sodomy, and died in prison in 1947.

Often it wasn’t just the faux-exotic performers but the impresarios who presented them who went by invented personae. The Victorian showman Guillermo Antonio Farini, aka The Great Farini, began his career as a tightrope walker in the late 1850s, went on to found the famous trapeze artists the Flying Farinis (including the stupefyingly agile Madamoiselle Lulu, who was actually his adopted son in drag) and invent the Human Cannonball act. Starting in the 1870s Farini presented widely celebrated African-themed variety show/freak show/circus extravaganzas featuring performers ranging from Zulu warriors to Pongo the gorilla. Farini’s real name was William Leonard Hunt; he was born in Lockport, New York, and raised in Ontario. He later claimed that when he ran away to join the circus he changed his identity so as not to bring shame and embarrassment to his straightlaced family. But no doubt the nice sound of Flying Farinis, as opposed to, say, the Highwire Hunts, had something to do with it as well.

The midways of the turn-of-the-century World’s Fairs–like the ones in Chicago in 1893 (also known as the Columbian Exposition), San Francisco in 1894 and Buffalo in 1901–were lined with ethnological displays of foreign and exotic cultures. The Chicago Exposition’s displays were organized in part by the great anthropologist Franz Boas, mentor of Zora Neale Hurston. Strolling fair-goers could take in recreated Eskimo and Dahomeyan villages, “[l]iving exhibits of Turks and Arabs, a ‘Singhalese Lady,’ ‘Javanese sweethearts,’ Penobscot Indians and their dwellings, and various other ‘tribes’ of people including Germans and Irish.” Note that exhibiting European “foreigners” side by side with more “exotic” peoples was quite common at the time. Their skins may have been lighter than most Africans’, but the Irish, Scots, Germans, Poles, Jews, Italians et al. were not yet considered as White as the purest, Whitest of White folks, the Anglos. An evolutionary progress was implied by how the cultures were lined up along the midway, starting with the most “savage” of them, the Dahomeyans and Native Americans, and culminating with the Irish and Germans, who most closely resembled–without quite achieving–the glory of American civilization. In fact, before 1900 anthropologists rarely if ever used the word “cultures” in the plural; there was only Culture, which was more or less synonymous with Civilization, which of course was White. One of the goals of Victorian anthropology was to figure out how all those other cultures stacked up below the White folks.

Americans, at least those who wrote for the papers, got the message that the Africans were as far as humans could possibly be from White civilization. The Buffalo Express noted that the African villagers were “as black as the ace of spades, black as ebony, black as dulled tar, black as charcoal, black as cinders, black as crows, black as anything that will convey to the mind absolute undiluted sunless, moonless, starless blackness.” A writer in The New York Times declared, “Nothing else I have seen conveys such an impression of wild savagery… the Indians are conventional citizens beside them.” Still, the writer went on, “they did not impress one as wicked or vicious any more than an animal is wicked or vicious.”

White Americans were amused to see how Black American fair-goers reacted to the Africans on display, and had much sport comparing their clothing and deportment to those of the “savages.” The humor magazine Puck celebrated the Chicago Exposition with a two-page cartoon by Frederick Burr Opper, “Darkies’ Day at the Fair.” It shows Africans and African Americans parading together, eating watermelon together and so on, indistinguishable but for their clothes, with an accompanying poem made up of verses like:

But a Georgia coon, named Major Moon, Resolved to mar the day, Because to lead the whole affair He had not had his way. Five hundred water-melons ripe, (The Darky’s theme and dream,) He laid on ice so cool and nice To aid him in his scheme.

As to how the savages felt about being gawked at, the women of the Dahomeyan exhibit in Chicago provide a humorous clue. Fair-goers who saw them joyfully singing and chanting assumed that they were expressing how delighted they were to be in America and how amazed they were by the technological wonders at the fair. In fact, when their songs were translated, they were more along the lines of, “We have come from a far country to a land where all men are White. If you will come to our country we will take pleasure in cutting your White throats.”

Along with the savages and foreigners, the Columbian Exposition put another subset of humanity on display: women. In a nod to the Suffrage movement, which was by then half a century old (and still a quarter-century away from achieving its goal), the Exposition featured a Women’s Building. The activities there, organized by a board of respected society ladies, included the expected displays of “feminine” arts and crafts like embroidery and jewelry-making. But there was also a lecture hall for a series of addresses on topics like “The Evolution of the Business Woman” and “The Progress of Society Dependent on the Emancipation of Woman.” There was one on “The Organized Efforts of Colored Women in the South to Improve Their Condition,” and three accomplished Black women–Fannie Barrier Williams, Anna Julia Cooper and Frances Jackson Coppin–spoke on “The Intellectual Progress and Present Status of the Colored Women of the United States Since the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Williams had graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music and the School of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., and was married to a prominent Black lawyer in Chicago. Cooper, who had been born a slave, was an Oberlin graduate and the principal of a Black high school in D.C. Coppin was also an Oberlin grad and principal of what would later be known as Cheyney State College. After hearing their remarks, Frederick Douglass declared his joy at witnessing “refined, educated colored ladies addressing–and addressing successfully–one of the most intelligent white audiences” he’d ever seen. It gave him hope that one day “this great country of ours will be possessed by a composite nation of the grandest possible character, made up of all races, kindreds, tongues, and peoples.” These three speakers hardly fit the common stereotypes of Black Americans, as seen in the Puck cartoon–and were in fact not presented as typical representatives of either their race or their gender. They were, rather, exemplars of the levels of civilization Blacks (and women) might achieve, given proper guidance and support. So the Exposition could truly claim to present the entire Darwinian ladder of civilization, from savages who were little more than animals to Irish and Germans and even Black women who seemed not so many rungs below Whites.

As soon as the Columbian Exposition ended, the Barnum & Bailey Circus hired a number of the exotic peoples who’d been on view there and put them on the road as the Great Ethnological Congress–continuing the genius for wedding science and show biz that had marked Barnum’s career (he’d died in 1891), and which took museum curators a century to understand and imitate.

This article by John Strausbaugh, from his book Black Like You: Blackface in American Popular Culture, published by Penguin-Tarcher.

REFERENCES

Lindfors, Bernth (ed.), Africans on Stage, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1999

Hennop, Jan, “Mbeki Calls 19th Century Europeans ‘Barbarians’ at ‘Hottentot Venus’ Funeral,” Agence France Presse, August 9, 2002

Behling, Laura L., “Reification and Resistance,” Women’s Studies in Communication, September 2002

Buzard, James and Joseph Childers, “Victorian Ethnographies,” Victorian Studies Volume 41, Number 3, 199

The Nelson Supply House

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on The Nelson Supply House

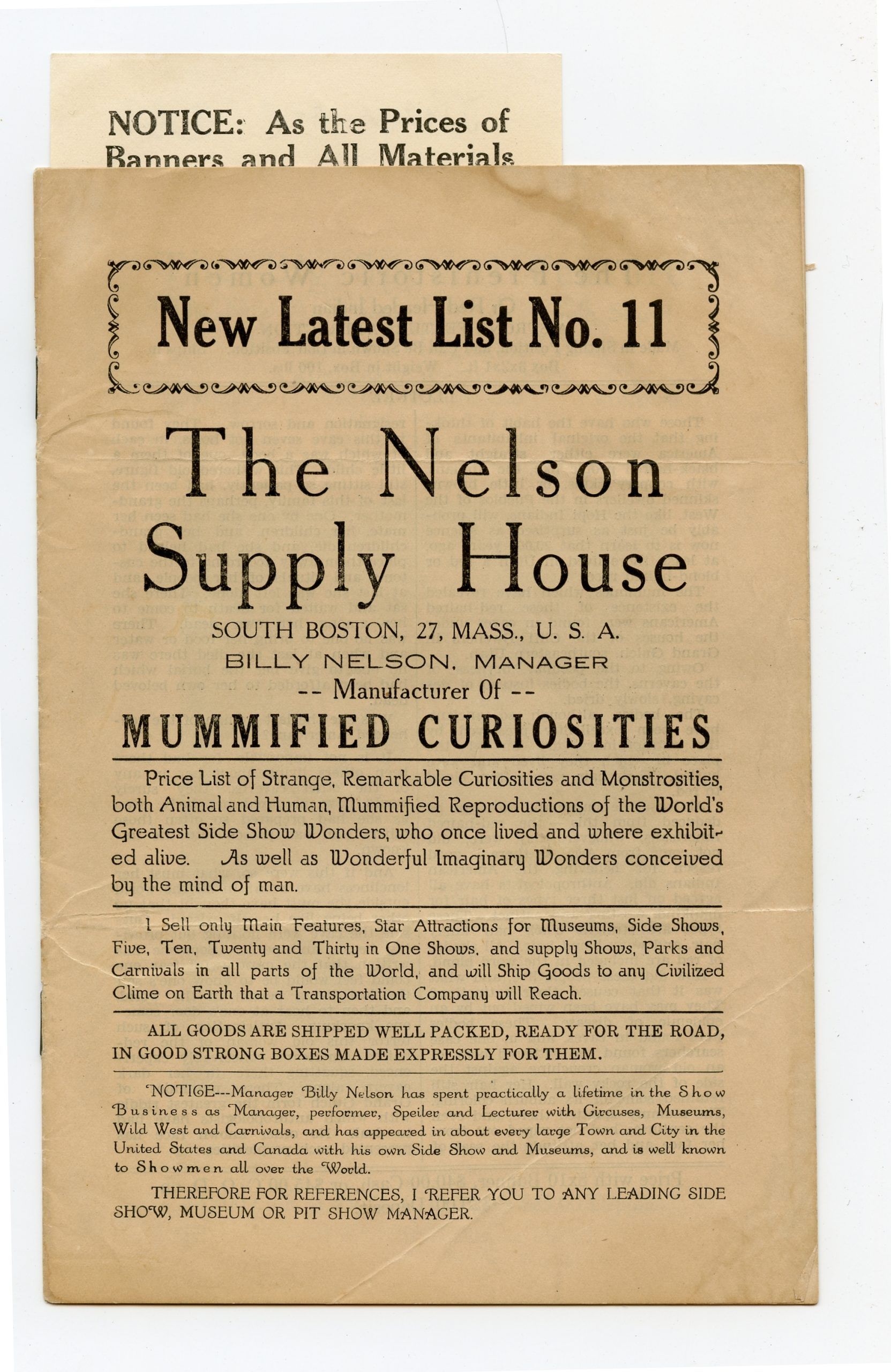

Of the old time gaff makers’ creations, The Nelson Supply House’s “Mummified Curiosities” are among the most gruesomely beautiful, most fully conceived attractions ever sold. The imagination and quality which went into creating them allowed Nelson to sell his creations “C.O.D. with the privilege of examination”(1). But proprietor William “Billy” Nelson didn’t just sell you a $25 papier-mâché gaff— he sold you a whole show. Supplying the banners, a scripted pitch, and the attraction itself, Nelson generated a whole business for the showman. All the would-be showman had to supply was the tent and the ticket-box.

That so many of these fragile creatures have survived 90-100 years intact is testament to their value as objects with continuing power to amaze. Up until the1990’s Ward Hall still carried a couple of Nelson mummies on his show.(2)

From about 1890 Nelson advertised his creations in The New York Clipper, including a “Wonderful SERPENT CHICKEN” and “CAT WITH TWO HEADS.”(3)

Nelson advertised in his “LIST No. 10” that “A Lecture is sent with Each Attraction,” and most of the attractions sold could be purchased with the banners reproduced above, or without.

Considering that the cost of the banner was an expensive $15 on this 1930’s list, perhaps many showmen had their own made, as even in the late 1940’s companies like George Bellis would sell you a pre-painted banner for as little as $9.(6) Certainly the quality of the banner art shown in Nelson’s list is eye-catching and original— so much so that these banners today could bring a small fortune with collectors.

In addition to Billy Nelson’s own mythological creations, such as “TWO HEADED CHINESE PA-LU-CA,” he also advertised several gaffed freak attractions which may be more familiar to today’s sideshow fan and historian. For in addition to creating “Strange, Remarkable, Curiosities and Monstrosities, both Animal and Human,” he also creates what he calls “Mummified Reproductions of the World’s Greatest Side Show Wonders who once lived and were exhibited alive.”

These “Reproductions” included “Antonio, The Italian Twins,” i.e. “The Tocci Brothers” (“Weight 125 lbs.”); “Labow, The Egyptian Double Boy,” i.e. “Laloo” (“This is a Money Getter….There is a Boy of This Kind Now Alive on Exhibition”); “The Grown Together Girls,” i.e. “The Hilton Sisters” (“We [also] have a small grown together girls about 3-1/2 ft. high, girls about 14 years old”). These appear in his list with photos of the real Tocci Brothers and Laloo, and could also be purchased with banners.

By selling “Mummified Reproductions” of living sideshow acts— which were no doubt billed on the outside as the real thing— Nelson embodied the wisdom that in sideshow the banner was often more important than the actual exhibit. Of course the Nelson “Mummified Reproduction” inside the tent had to be pretty good, otherwise the quantity of beefs might bring the show more heat than it needed.

While mass-producing his gaffs could have made Billy Nelson rich, little is know about his actual enterprise. We only know that he made a good enough living from it to give up “”practically a lifetime in the Show Business as manager, Performer, Speiler and Lecturer with Circuses, Museums, Wild West and Carnivals….”(7)

While Nelson was without doubt a talented artist imbued with imagination and skill, he was, if nothing else, a showman first. He understood that it was ultimately about getting the nickels and dimes and quarters from the marks. And since the show was exactly just that, it was easy for him to advertise his “Two Headed Hockadola” as:

“…a thousand miles ahead of dancing girls, wild men, or snake eaters. A dead man can get money with it.” (8)

And a living man could probably do pretty good too.

— D.B. Doghouse, December 2005.

REFERENCES (see below)

This page last updated December 26, 2005.

(1) “LIST No. 10,” The Nelson Supply House. South Boston, MA (ca. 1930)

(2) Stencell, A. W. “Seeing Is Believing: America’s Sideshows”. Canada: ECW Press, 2002. p.41.

(3) Ibid. p. 39.

(4) Ibid. p. 40.

(5) John Robinson, Sideshow World (www.sideshowworld.com)

(6) In conversation with Ward Hall, September 2005.

(7) “LIST No. 10,” The Nelson Supply House. South Boston, MA (ca. 1930)

(8) Stencell, A. W. “Seeing Is Believing: America’s Sideshows”. Canada: ECW Press, 2002. p.40

Shown below: The details on this Nelson mermaid show why his work was considered the best in the business. From 1909 (4) until at least 1938, (5) Nelson continued to sell such creatures (and banners) as KING JACK-A-LOO-PA, The

and The Six-Legged POLY-MOO-ZUKE, The Centipedian Wonder:

and The Devil of The Ocean, THE BIG SEA HORSE:

The “Extraordinary Japanese Mermaid” of the Milwaukee Public Museum, by Karl Wolff

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on The “Extraordinary Japanese Mermaid” of the Milwaukee Public Museum, by Karl Wolff

Is it any wonder that the feejee mermaid is the official mascot of showhistory.com? Granted ours is a very strange, glass-eyed, cute(?) version of the form imitated and re-imagined a thousand times since Barnum. Nonetheless as classic objects of wonder, author Wolff reaffirms through his scholarship that these “little beasts” are still very much part of our culture. For more information on Feejee’s and their ilk, see our page on Gaffs.

The “Extraordinary Japanese Mermaid” of the Milwaukee Public Museum The Feejee Mermaid: The Milwaukee Taxidermied Treasure & Others

by Karl Wolff

Introduction

The Feejee Mermaid represents humanity’s attempt to deal with its myths. This physical manifestation of ancient myth harkens back to other works of art, but over time became a myth in its own right, resurrected in the modern sideshows. Modern sideshow professionals keep the myth alive, entertaining crowds and preserving a specific part of American cultural heritage.

Throughout the centuries, there have been alleged mermaid sightings and exhibitions of mermaids before the Fejee Mermaid. The Fejee Mermaid (note the spelling) became Phineas T. Barnum’s greatest humbug and remains a staple in the Barnum literature. The humbug tradition is carried on with the Milwaukee Public Museum’s “Japanese Mermaid” (as seen above). Today modern taxidermy artists make “animal gaffs” for sideshows and a general audience. On the surface, their profession appears peculiar, but they actually carry on a tradition spanning hundreds of years in supplying sideshows and carnivals with fake animals.

Because the “Japanese Mermaid” is a taxidermy hybrid— a combination of fish and papier-mâché— it presents a series of challenges in a number of areas, including: cataloging, conservation, and collections. The fake animal was constructed out of the cheapest of materials for the entertainment of the sideshow audience, but has mythological, cultural, and historical associations that make it one of the more valuable and intriguing artifacts of the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Mermaids in Mythology

The mermaid is a mythical creature. According to Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, the mermaid was a “fabulous sea marine creature, half-woman and half-fish, allied to the SIREN of classical mythology, [that] probably arose from sailor’s accounts of the dugong” . An Irish mermaid is called a merrow, from the Irish word murbhach. These merrows “were believed by Irish fishermen to forebode a coming storm.” The sense of foreboding is also associated with the Sirens in Homer’s Ulysses. Unlike mermaids, sirens were “half-woman and half-bird” , but remain mythical figures that seduced travelers into disaster. Siren comes from the Greek word seira meaning ‘rope’ or ‘entangler’. Besides Irish and Greek mermaids, similar mythical creatures exist in other cultures as well. Jan Bondeson mentions Artergatis, the “fish-tailed Phoenician moon goddess” .

The sea’s power and unpredictability are embodied in these figures, whether as a sea goddess, siren, or mermaid. This will become important later in history as the competing forces of myth and tradition collide with the yearning for empirical proof and the growing reliance on science as a method of explanation. The Feejee Mermaid will become emblematic of this tumultuous reassessment of knowledge, science, and mythology.

Mermaid Sightings and Early Mermaid Relics

Prior to the appearance of the Feejee Mermaid in 1822, mermaids made their presence known to Western Europeans. These spectacles came in two varieties: sightings and relics. While the historical accuracy of the sightings is dubious, these phenomena are instrumental in understanding how the public will later react to The Feejee Mermaid.

The mermaid sightings, while easy to dismiss, are analogous to UFO sightings of the present day and other cryptozoological encounters (e.g.: Bigfoot, Chupacabra). What is missing from these encounters is physical evidence. Bondeson cites examples of contact with living mermaids. The popular imagination had yet to be debunked by science, so it was natural to believe these tales. In 1403 a “living mermaid [was] caught off Edam, Holland” . In 1531 a live mermaid was caught off the Baltic coast and was sent as a present to King Sigismond of Poland.

FIGURE 1: A contemporary drawing of Barnum’s Feejee Mermaid, “The Eades Mermaid” (Source: Olalquiaga).

Encounters were not limited to European waters. In 1560 Jesuits in Ceylon caught seven tritons and seven mermaids. Unfortunately, Bondeson does not have much detail about these early “live mermaids.” The lack of details can be attributed to the lack of primary sources and the lack of physical evidence. Given the wide array of marine life, it would be plausible that the Jesuits caught a vaguely human-looking sea animal and gave it the name “triton” or “mermaid”. These early encounters reveal the difficulties of animal classification.

In 1565 a “Mermaid skinne” is exhibited, originating from Thora, a town by the Red Sea. A mermaid also was exhibited in a church in Swartvale, Holland in 1660. Classification becomes a primary issue when scientists came in contact with the creatures of mythology. In the 1700s, the anatomist Thomas Bartholin possessed a hand and tooth of Sirenica danica, which later sold at public auction in 1826. The anatomist Carl Linnaeus, the inventor of binomial nomenclature, saw two specimens. The first was a mermaid caught off the coast of Nyköping, Jutland. Another specimen, a “siren” from Brazil, was kept in a museum in Leyden and appeared in the tenth edition of Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae. But this classification of mermaids and sirens is not out of character with taxonomy, since scientists have given animals names like hydra, medusa, and devilfish.

The first mermaid to tour in Britain was in 1737. A live mermaid was exhibited in the market of St. Germains as late as 1759, while two tritons were caught off the Isle of Man in 1800, and well-publicized mermaid sightings were reported in 1809 and 1812. In 1809, more than a decade before the appearance of the Feejee Mermaid, an exhibitor is charged with fraud for displaying a fake mermaid.

Fraud will become a major issue with the appearance of the Feejee Mermaid. The battles between science and mythology, elitism and populism, entertainment and education will be fought in the first half of the nineteenth century. The battleground will be the animal gaff in the form of an ugly mummified mermaid.

The Fejee Mermaid

While literature on earlier mermaid sightings and exhibitions remain sparse, much has been written about the Fejee Mermaid (note spelling). Its association with Phineas T. Barnum is responsible for its well-known status, especially among sideshow professionals and taxidermists. Barnum himself called the Fejee Mermaid “The most famous put-on of all.” Olalquiaga asserts that the fake mermaids were “surrogate relics of ancient dreams” . Its immense popularity reflected “a century obsessed with empirical proof” , functioning in a strange ritual territory as both scientific specimen and mythological relic. Here was material proof that the ancient myths were true. P. T. Barnum would later manipulate truth and reality, destabilizing both in the name of entertainment. But the story of the eponymous Fejee Mermaid is about more than Barnum’s showmanship.

While traveling in Indonesia Captain Samuel Barrett Eades, an American working for the Boston commissioning house Perkins and Co., arrived in Batavia. As one-eighth owner of the merchant vessel Pickering, he was beholden to the majority owner of the vessel, a man named Stephen Ellery. Then Eades saw a two and a half foot animal whose strangeness rivaled its ugliness. As an experienced sailor, Eades must have been familiar with cartographic maps and the monsters depicted in the margins. What he saw was one of those monsters, only this time he could see it with his own eyes and without the bias of a cartographer who heard sea tales secondhand.

FIGURE 2: A contemporary drawing of Barnum’s Feejee Mermaid, “The Eades Mermaid” (Source: Olalquiaga).

Sources disagree on length, but the literature is unanimous in what made up this alleged Mermaid. Its tail was from a salmon, while the head and torso came from a female orangutan (Figure 1). The eyes were artificial and the nails were either horn or quill. But Eades thought it was genuine, which provoked him to sell the ship and buy the Mermaid for 5000 Spanish dollars or 1200 pounds. He thought he could exhibit the Mermaid and make the money back by charging admission to see the wonder.

The Fejee Mermaid was first exhibited in Cape Town in early 1822. It next appeared on exhibit in the Turf Coffeehouse in St. James’s Street from September 1822 to January 9, 1823. Paul Semonin states that “Inns were regarded … for upscale viewing,” [but] “The cheapest shows were those of itinerant showmen who set up their displays in the streets near taverns or coffeehouses.”

Men of science disregarded the exhibition, but the general public thought it was genuine. One of these men was an assistant to the eminent London anatomist Sir Everard Home. Home would later be famous for examining both platypus and mermaid. William Clift, his assistant, debunked the Mermaid on September 21, 1822. Harriet Ritvo asserts how “Exhibited mermaids … concretely challenged the established order of nature, which offered them no places.” The issue of place would later become problematic for scientists attempting to classify the mermaid. When the exploration of Australia was in full swing, Charles Gould stated “many of the so-called mythical animals … come legitimately within the scope of the plain matter-of-fact Natural History.”

Since taxidermists were producing animal gaffs for sideshows (Figure 2) at this time, the scientists thought it conceivable for “an unscrupulous taxidermist” to attach a fake beak onto another animal, possibly a beaver or otter.

Olalquiaga sums up the bizarre status of the Fejee Mermaid: “By the mid-1800s, then, mermaids have turned into the most confusing of beings, adding their amphibious nature this triple crossover between fact and fiction, life and death, real and fake.” When Clift debunked the Mermaid in 1822, he took away the source of wonder and, in turn, Eades’s business.

By November 1822, in a last ditch effort at credibility; Eades advertised that Home said the Mermaid was genuine. By December of that year, the public had lost favor of the exhibit. On January 9, 1823, Turf Coffeehouse shut down the exhibition. During the next year, it toured the provinces, and then from 1825 to 1842 its whereabouts were unknown.

Article by Karl Wolff, master’s student in Public History-Museum Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. During the summer of 2005 he completed an internship at the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida.

Leonard Trask “The Wonderful Invalid”

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on Leonard Trask “The Wonderful Invalid”

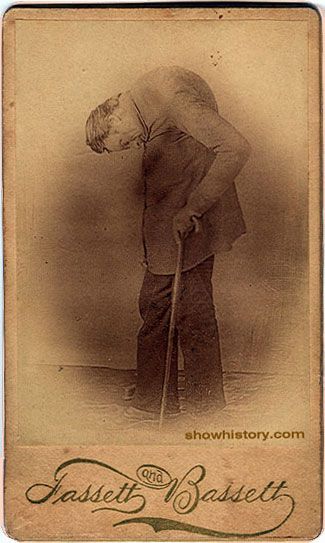

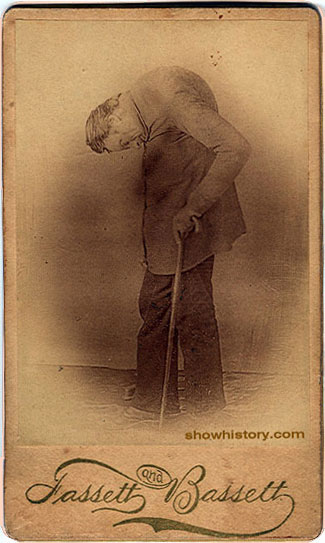

Leonard Trask “The Wonderful Invalid”

In the strange history of those who made a living from an acquired deformity or mutilation, perhaps none is stranger, or more ill-starred than Leonard Trask. Born in Hartford, Maine on June 30, 1805, Trask acquired his odd contortion of neck and spine in 1833, when a “luckless hog” took fright, and ran beneath his horse’s hooves. Flying over his horse’s neck onto his own neck, Trask eventually crawled back to his home on a journey that took several days. Amazingly, Trask didn’t snap his spinal column, though there is some evidence that landing on his head was not a lesson for future caution.

Trask challenges the very boundaries of what constitutes a performer. Though the distinctions between the genres of performers is often pliable, in our delving into the history of the business we find that “the stage” can be found in many guises. Whether circus ring, sideshow bally stage, vaudeville stage, or “the stage of the streets,” there is only one constant– the player who is paid to perform. Trask made his living after his injuries on the streets and byways of towns throughout New England. His story is one told over and over by performers here, although perhaps rarely as full of pathos.

Bedridden for months after his his initial accident, and as disastrous as it was for his health, for years, often in excruciating pain, Trask continued to do torturous labor— logging trees in the Maine timber swamps, even in winter without adequate shelter. This abuse caught up to him a year or so later when “the neck and spine …began to curve, and he began to bow forward.”

In the 50 page pamphlet first published in 1857 Trask names twenty-two doctors who tried nearly every harrowing 19th-century cure imaginable. Everything from cupping to bleeding, from lobelia emetics (Lobelia inflata, also known as Indian tobacco or pukeweed), to blistering the neck with heat, from deep incisions cut on both sides of the spine to lying in a bed of boiled potatoes, from inserting a strip of linen (a seton) beneath the skin with needles, to lying in a tub of cold water and having heated stones tossed in– none of this halted what Trask calls the “drawing of the spine into a circular form.”

In between treatments, though urged to seek charity, he continued to work, until in 1840 he fell from a load of hay. Now crippled further, he consulted more doctors as far away as Boston, but soon his case was judged “hopeless.” As grievously described by Trask himself, “his neck and back have continued to curve more and more, every year drawing his head downward upon his breast till there appears but little room to press it farther without stopping entirely the movement of the jaws.”

Able to perform little labor but hoeing, Trask took to peddling house to house, though he admits that he often scared young children, women and animals, who were “defeated by his uncouth figure and deformity.”

Then in 1853, again, companion misfortune: as “being in continual danger of accidents on account of his inability to discover objects any distance before him,” Trask was thrown from his wagon, breaking four ribs, and his collar bone. When healed he took to walking, though this was also not without danger, as he was “unable to see but a few feet before him without bending backwards.”

Throughout it all, this self-described “child of sorrow” staved off “pauperism,” raised 7 children while “sustaining a feeble wife” who nursed him “till her health, too, was gone.”

Though he came to it late, after much travail, Trask ultimately falls into that category of human anomaly neither born into it, nor found seeking its bare sustenance (see “made freaks”), but nonetheless he is marked by a final aim to make coin from his misfortunate deformity. That men would pay to see and read of others injured so unusually by fate has been borne out by a history of those exhibiting themselves after some tragedy miraculously survived. Those that sold their likenesses and histories to support their woefully acquired conditions include the “Broken Neck Wonders” like Barney Baldwin, those left limbless by accident, and many wracked by disease that left their faces and bodies askew.

That disability can “earn” is today considered by some, who misunderstand the history of shows, as always a form of simple exploitation. But this simplification is disproven by Trask— who for so long through super-human endurance avoided the inevitable path to poorhouse, prison, or asylum— who was to succumb finally instead to “the road,” i.e. showbiz, exhibition, the sale of pitch books and photographs, i.e. so-called “exploitation” of his bodily wares that allowed him to survive.

The objects produced for Trask to sell which are shown above have survived these 150-plus years because Trask fascinated and continues to fascinate, because he offered and sold something of value— his deformity and morbid suffering. Humans in their most exalted moral role as protector of the weak cannot dispel this human interest in living human anomalies, and usually those on “the high chair” have no interest in the weak except to protect them from others, who supposedly unlike their noble selves may seek to exploit their deformities for monetary gain. Trask did not choose to live his tale of woe, but he did finally choose to exhibit it to earn his living.

For the entrepreneurial freak/handicapped/crippled/human oddity/mental deficient a way to survive was to exploit oneself, or even to be exploited by showmen. Trask was able to choose, and chose to exploit himself:

On account of his strange and peculiar form, many show-men have attempted to hire him in order to take him before the public for exhibition.His decision not to exhibit himself for showmen, but to exploit his own deformity himself, was made without effort, as this monolithic sentence from his pitchbook makes clear:

His reply has ever been, that his misfortunes and afflictions, his pains and sufferings, were his own; his singular figure and deformity was his own,– and as it has pleased God so to afflict him, that he had become a living, human curiosity, and a wonder to his fellow men, he would sell or hire himself to no man, to become a source of speculation in their hands– that though in his physical appearance he scarcely bore the resemblance of humanity, yet through the benignity of a kind of Providence, the ‘man within’ had been left unimpaired; and if his singular form presented to the mind of his fellow-men, a subject of curiosity, wonder, interest or instruction, the sight should become a source of profit to no one but himself.In a modern diagnosis, Trask has been described by British rheumatologist, Malcolm I.V. Jayson, to have written the first American description of “Ankylosing spondylitis.” This condition is the same as J.R. Bass “Ossified Man” was said to have had. The malady is best explained as a type of inflammatory arthritis which causes excess bone to form in the joints, and it often immobilizes those afflicted.

Though we may understand the medicine and disease behind Trask’s case, his story and visage nonetheless continue to fascinate us with its harrowing human tale of extreme misfortune, deformity and neglect.

(See pamphlet, “THE LIFE AND SUFFERINGS OF LEONARD TRASK, The Wonderful Invalid.” [PORTLAND, MAINE: Printed by David Tucker, 1858].) (See Carte D’Viste of Leonard Trask, circa 1863. by FASSETT and BASSETT, Lewiston, ME.)

Hunger Artists: Fasting Wonders (by Rubin De Somer)

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on Hunger Artists: Fasting Wonders (by Rubin De Somer)

If the Hunger Artist is remembered at all in the United States it is perhaps only because of that great Czech writer, Franz Kafka. In his short story, A Hunger Artist (Ein Hungerkünstler), published in 1924, Kafka’s performer finds himself performing at the circus in the twilight of his career. He discovers that the public is no longer interested in the art of starving oneself for the entertainment of the masses.

While the Belgian author, Ruben De Somer, writes in his article below that the first hunger Artist of the 19th Century was American, it appears that many of its most famous performers and largest audiences were European.

by Ruben De Somer

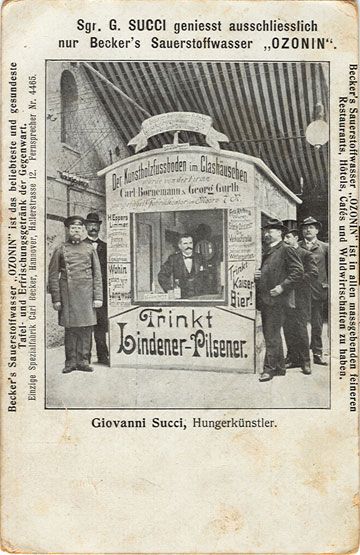

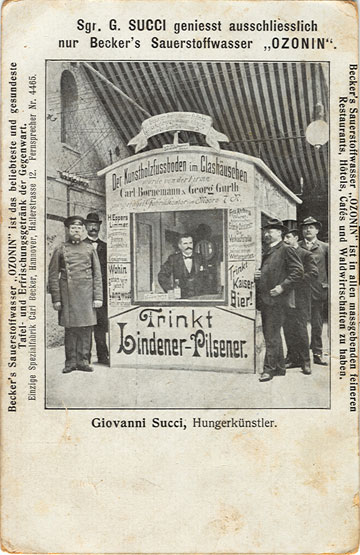

Long before late-19th and early-20th century “Hunger Artists” like Tanner, Papus and Succi roamed the carnivals, fairs and Variety theatres, a slew of predecessors paved the way.

Most European countries had their own fasting wonder. Their main show activity was lying in a bed, slowly dying of hunger while the masses crowded around them. Most of these people claimed to have been fed by God.

In the U.K. Martha Taylor (17th century), Ann Moore (19th century) and the Welsh “Fasting Girl,” Sarah Jacob (19th century) earned their living, living on air. In Austria the 50 year old carpenter Wolffgang Gschaidter lay starving for more than 15 years (17th century) and in Switzerland Apollonia Schreiert fasted her life away (17th century) [1]. Bernard Cavanaugh reputedly fasted for more than 5 years until he was convicted for being a hoaxer and vagrant. Even in prison he didn’t eat: “the surgeon of the prison has signed a declaration that Cavanaugh has never touched, since the 29th of November, in 9 days time, food or drink, despite this he stays healthy in body and mind.” [2].

Francisco Cetti (late 19th-early 20th century) was a Norwegian [3], who exhibited himself in Berlin in 1887 but during this fasting session he quit after only 11 days. [4]. A fellow Scandinavian was Mrs Christensen from Denmark who had to leave the London Royal Aquarium after 17 days instead of the 30 days she had planned [5].

The most well known fasting wonder and the main inspiration for the late 19th century revival was Dr. Henri Tanner, an American. [6] Another American was the wealthy Brooklyn resident Austin Shaw who did it because he wanted to– he had read it in a book. [7]

The German fasting wonders also had a long history of survival on divinity. The oldest known case was the wonder girl Margarethe Weiss of whom a pamphlet exists from 1542. The “Daughter from Cologne” exhibited herself in a tavern in 1595. Another famous fasting wonder was Eva Vliegen (17th century). More recently there was Therese Neumann (20th century) with the final chapter in Germany told by “Heros,” real name Willy Schmitz, who performed until the 1950’s. His most famous feat was a performance in the Zoo of Frankfurt, where he stayed in a glass cage for 56 days. [8]

Belgium has had very few examples, though the most famous one was Louise Lateau who fasted for 12 years and then died in 1883 [9]. Earlier an 18th century woman was carried around on a carriage, forced to pray for mercy in front of the churches in Antwerp, Belgium [10]. In 1886 a man from Brussels, Mr Simon also wanted to go for a world record of fasting but quit after a mere 12 days [11].

In France there was Papus (19th-20th century) [12], Alexander Jacques (early 19th-late 20th century), and Jeanne Balam (17th century).

Italy had three 19th century fasting wonders— Merlatti [14], Succi, and Ricardo Sacco [15].

In Holland there were the performers Maria van Dijck (18th century), Barbara Kremers (17th century) [16], and Engeltje van der Vlies (19th century). But of all the Dutch fasters, Engeltje van der Vlies was perhaps the most famous. Below we will look at her through the eyes of the contemporary press, and see her compared with many of her fellow hunger artists.

Engeltje van der Vlies

“Engeltje van der Vlies was born in Schiedam [Holland] on the 20th of August 1787 and is living in Pynacker near Delft, whose life has been dragging on without beverage and food since 1820, is currently very indisposed, several times the doctor has been forced to bleed her. Currently people think, more than ever, that her life thread will be severed, which when this has happened, will lead to weighty discoveries for scientific practices.” (Gazette van Gent, Belgium April 11, 1847)

And another author, writing from Amsterdam several years later:

“For a long time people haven’t heard anything of Engeltje van der Vlies, from Pynacker near Delft, that most peculiar woman, who hasn’t eaten anything since 1818, and since March 1822 hasn’t drunk anything. Many think she has passed away. Meanwhile she has celebrated her 66th birthday and her continuous existence can be seen as a miracle. People will recall that in 1826, a report was made by a medical commission regarding her, the result of which was that Engeltje van der Vlies was watched for 4 weeks by 4 trustworthy persons around the clock, and they declared under oath that she hadn’t eaten anything, food nor beverages.

“Since the aforementioned research about 27 years have passed, and more than 35 years in which she hasn’t eaten and more than 31 years that she didn’t drink anything: but still the art hasn’t succeeded in explaining why she was able to maintain her life force in such a marvellous condition. With the lacking of one of the greatest pleasures of life, sick and poor, she’s most of the time cheerful and happy, and rests good-natured and resigned in her fate, the so-powerful support; her Christian religion gives to her true follower so spacious.” (Gazette van Gent, Belgium, September 09, 1853)

And then appearing one week later in the same publication:

“Many persons have doubted the report that we’ve given a couple of days ago regards the girl, Engeltje van der Vlies, living in Pijnakker near Delft, in Holland, who hasn’t eaten for more than 32 years. We can insure our readers that the whole history is very true. A person who has even talked with this miraculous girl, gives us the following information:”

‘She lived with the reverend of Pijnakker (an hour and a half from Rotterdam and the Hague) as a servant girl. Her brother, a deserter of the militia was caught by the gendarmes. As a result this shocked her so much that she stopped eating. At first they didn’t pay attention to it, they thought it was a natural result of her fear. However when it took several days in succession, they noticed it much more. Doctors were consulted all over the country without avail. None of them could explain where the remarkable condition of the girl came from; none of them could explain the change which had taken place in her organization.’

“For a couple of more years she could still drink.” (Gazette van Gent September 16, 1853)

Another writes from Delft of van der Vlies:

“The famous Engeltje van der Vlies, who several newspapers recently discussed, as she allegedly had lived without food or liquid, has died yesterday in Pijnakker. As a result a medical examination took place, in company of several specialists, and so one says in supervision of the provincial commission of medical health research, the opening of the body has taken place of which the result is: at a certain height of the gullet (being the Cartilago Cricodea) a fleecy stricture was present, which wasn’t that hard, or lessening the workings of the gullet, that she couldn’t pass any solid food, she could certainly pass liquid food very easily in huge amounts. In the intestines newly freshly formed faeces was present and this was a clear proof that she had eaten recently, there were even food remains in the upper part of the intestinal tube(the microscopic and chemical research has to determine which food), and finally there were no deviations which could support the probability that no food had been used, or that the feeding had taken place in a supernatural way.” (Gazette van Gent December 12, 1853)

Fraud, Religion, and Medicine: Motives of the “Fasting Wonders”

Why did they do it? Some of them probably really did it out of faith, but in most cases profit was the reason behind it all. If you wanted to visit such a miracle, whether it was in a tavern, a fair or at their house, you had to pay. “The Fasting Wonder of Tutbury,” Ann Moore, for instance, managed to collect 400 pounds in the beginning of the 19th century. For a woman who used to be sustained by alms this is a huge sum.[17]

The Belgian, Mr. Simon claimed he did it for humanitarian reasons. Simon explained that his fasting was as an example for miners who might be trapped in a mine cave-in— showing them that they could stay alive a lot longer without food. The fact that he would earn a nice salary of 5 Franc performing also helped things along.[18] At one point in time Succi started a 40 day fast, saying his cash-flow was low, and he needed to acquire money and lots of it.[19]

Not all miracle fasters had a religious background. Some did their deeds for reasons of health, and others did it because it was their job. The American Henri Tanner wanted to prove that one could keep on living without food for a long time and performed in Clarendon Hall in New York. For 14 days he lived without food. [20] In a way he was a trendsetter because many followed his lead. His most famous contender was the Italian Succi.

The religious aspect of fasting was for a long time en vogue. Engeltje had been granted her powers for survival by divine intervention. She wasn’t the only one. The same was claimed by Martha Taylor, Eva Vliegen, Louise Lateau, Therese Neumann, and Wolffgang Gschaidter. [22]

In some cases the viewer was given a show, but most of the time the fasting wonder just lay there dying. However, most of the time the faster told his or her story to the visiting public. The Austrian Wolffgang Gschaidter was even promoted as the symbol of the city Innsbruck and the public was invited to come and see him at the local church and give an alm. (‘Makes me wonder about the weight of the people from Innsbruck’).

Another important element was that many invited doctors to prove the public that their “wonderous condition” was real. This the fasting wonders shared with many other types of “exhibited people”.

Engeltje, Henri Tanner, Succi, Martha Taylor, Sarah Jacobs, Francisco Cetti all were examined by the medical profession. Mr. Simon had both a dentist and a medical Doctor at his side during his performance, as well as 45 other people who had to watch that he didn’t do anything fraudulent. The only strange thing is that Cetti gained weight during his performance and was exposed as a fraud which brings us to following paragraph.

Just like many other exhibited people, fraud was a common feature of the performance. Engeltje, about whom we’ve just read, got her food through a small hatch which was hidden behind her bed, and through which her accomplice kept her nourished. Barbara Kremer was exposed by the Dutch doctor Johannes Wier (1515—1588). The Antwerp woman had to visit several churches and pray for forgiveness. The famous French magician and occultist Papus was also unmasked during one of his performances in Germany. [23] Succi as well as Tanner were also accused of fraud during their long careers. [24] Sarah Jacobs died before they found out the truth.

Many exhibited freaks and human oddities were the result of “Maternal Impression” according to literature and advertising which accompanied their exhibition. In the case of Engeltje it was her mother’s fear resulting from the capture of her brother. [25] It is not known whether other fasting wonders used the “Maternal Impression” explanation to highlight the reasons behind their condition. However such a miraculous shock did add to the attraction of these performers and could help explain to the audience in a “scientific” manner why the act chose to take this path.

The fasting wonders also sold pamphlets just like many other exhibited people. Martha Taylor, for example, had Thomas Robbins, a balladeer, write and publish a pamphlet about her claiming that she had fasted for more than 40 weeks through divine intervention. [26]

Did they really eat or drink nothing? In most of the cases they did drink. Succi for instance used a special potion which probably contained some kind of narcotic.26. If you look at the postcard on top of this page you will see that he promoted some kind of “sauerstoffwasser” or oxygen rich water called Ozonin. Other were real frauds, and others only drank water to avoid drying out. Especially those who exhibited themselves for medical purposes.

Conclusion

Looking back at our miraculous brethren and sisters, we can say that most of them were people who were in need of attention, whether it was for financial reasons, religious or medical.

This need for attention is an important incentive, as we turn on the television and discover that the fasting wonder still exists. Gandhi as well as many other used it as a way to attract attention, and to gain their political goals. Yesterday (April 6, 2005) when I turned on the my televison I heard the story of 30 Kurds who had barricaded them in a church and were fasting. How little has changed?

REFERENCES:

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

(Gazette van Gent 12/10/1841

-

http://tdplata.tripod.com/historia/, Cetti was in a later stage in his career also an aeronaut, being a airballoonist at one time in Buenos Aires

-

Gazette van Gent, 03/26/1887

-

Gazette van Gent, 10/14/1888

-

Gould, G,.M., W.L., Pyle, Anomalies and curiosities of medicine, New York, Julian Press,1956.

-

Gazette van Gent, 07/3/1905

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht. museum dr guislain, Gent, 10/24/1991 – 01/19/1992.

-

Didry, M., Wallemacq A., Levenschets van Louise Lateau, de wondendraagster van Bois d’Haine. Leuven, Nova et Vetera, 1921

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

Gazette van Gent, 12/1-2/1886 and 12/13-14/1886

-

Gazette van Gent, 11/22/1896

-

Gould, G,.M., W.L., Pyle, Anomalies and curiosities of medicine, New York, Julian Press,1956.

-

Gould, G,.M., W.L., Pyle, Anomalies and curiosities of medicine, New York, Julian Press,1956.

-

Gazette van Gent, 03/06/1906

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

Gazette van Gent, 12/1/1886

-

Gazette van Gent, 03/18/1886

-

http://www.br-online.de/wissen-bildung/kalenderblatt/juni/kb20000628.html

-

London Illustrated News, 1880, p. 133-134. or L’Illustration Européenne 09/4/1880

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

Gazette van Gent, 05/13/1904

-

Gould, G,.M., W.L., Pyle, Anomalies and curiosities of medicine, New York, Julian Press,1956.

-

Gazette van Gent September 16, 1853

-

Allegaert,P., Cailliau (red), Vastenheiligen, wondermeisjes, en hongerkunstenaars, Een geschiedenis van magerzucht.

-

A mocking report of this potion, which could be bought by everyone, was published in “L’Illustration” from 4/06/92, p. 486.

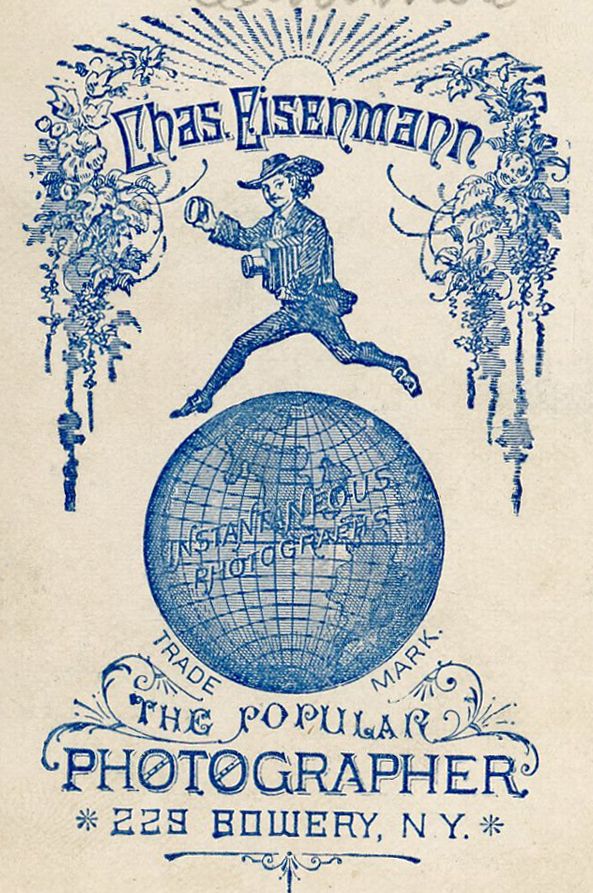

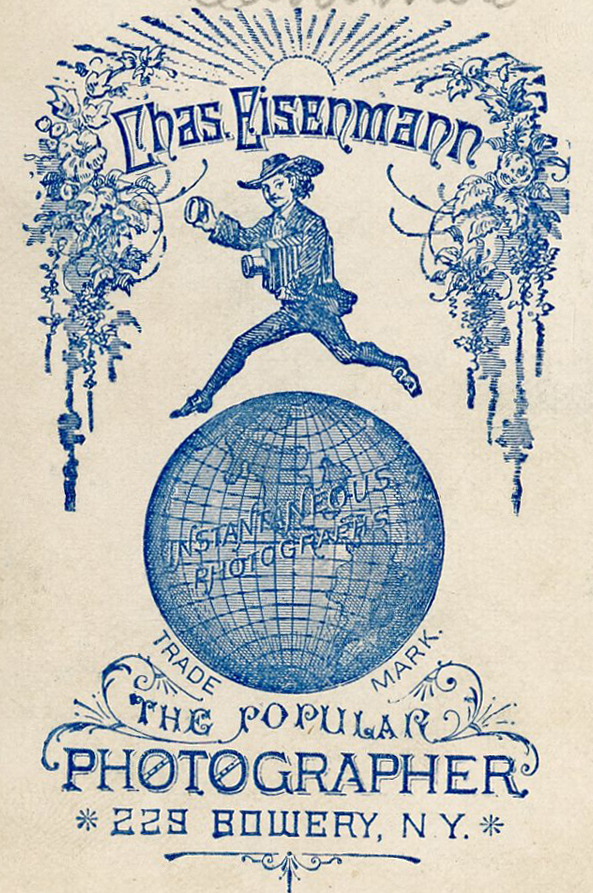

Charles Eisenmann’s Mounts and Backmarks

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on Charles Eisenmann’s Mounts and Backmarks

Cataloguing photographer Charles Eisenmann’s various and sundry cardboard mounts– both fronts and backs of Cabinet Cards and Carte De Visites– has been a pet (sideshow nerd) project of mine for many years. Knowing the mounts and their dates of usage may eventually prove useful to other collectors and historians in dating images.

Because the present collection does not offer a wide enough variety of examples used throughout Eisenmann 30-plus year career, I am soliciting help from other owners/collectors of Eisenmann Carte De Visites and Cabinet Cards. If you have dated Eisenmann photos, or if you have a mount which is different than the ones listed below, please email us using the contact form.

Also, certain mounts may have been reprinted and used over a wide variety of dates. Likewise, some mounts may have been used for a while, abandoned, and then again used for a time again. Finally, Eisenmann probably used mounts interchangeably from a large reserve of different styles.

Below is a selection with approximate dates, and exact dates if recorded on the actual photo.

I’ve also ranked reliability of these dates between 1 and 10, which is a subjective criteria once you reach below a ranking of ‘8’.

Rankings and their explanations:

10: If the signature of a performer is present along with an written date on the same hand, then I rank that date reliability a ’10’. Another ranking of ’10’ would be if the date is actually printed on the card, which did not happen very often. The only other instance of a ’10’ I’d allow is if a certain performer or group of performers only appeared for one year, but the card is not marked with a date. This must be confirmed by a route card, a blurb or advertisement in The New York Clipper, a mainstream contemporary newspaper, or a “reliable” book which cites a primary source. Most sideshow books throw out dates and don’t cite sources, and these are dealt with below.

9: A ‘9’ would be if a seemingly contemporary hand recorded the date, i.e. “I saw this fat lady at the dime museum June 11, 1886.”

8: An ‘8’ is a card which is dated on the back or front, but it is not clear who wrote the date, but the writing appears to be contemporary with the card. Another ‘8’ rank can be had by a secondary source, i.e. a book or other published source which quotes a date found on an example of the same photo and mount.

7: A ‘7’ is dated by another exact mount or back mark which is dated on another photo of a different performer with either a ‘9’ or ’10’ ranking.

6: A ‘6’ is dated by another very similar mount or back mark which is dated on another photo of a different performer at either ‘9’ or ’10’.

(To be continued, work in progress……..)

Sideshow Banner Painters

Written by Doghouse on . Posted in Uncategorized. No Comments on Sideshow Banner Painters